This final Friday of June found us gathering again, this time with the fantastic Erin Richardson, PhD of the practice Frank & Glory, a museum services firm that supports diversity and sustainability in museum collections. Erin’s presentation kicked off with the stirring statement (borrowed from a former professor), “Everything is on a path to death.” With that cheery exclamation (!), we were launched into an extremely thought-provoking exploration of museums and archives and a lively Q + A. Here are a few topics we covered.

Conservation Is About Slowing The Time To Death

Erin began by walking us through some of the fundamentals of museums and museum management. For centuries, these institutions have been built to be both temples to the wealth and largesse of individuals, families, and institutions, while also serving as a means for us humans to tell a story about who and what we have been and what is and was important to us.

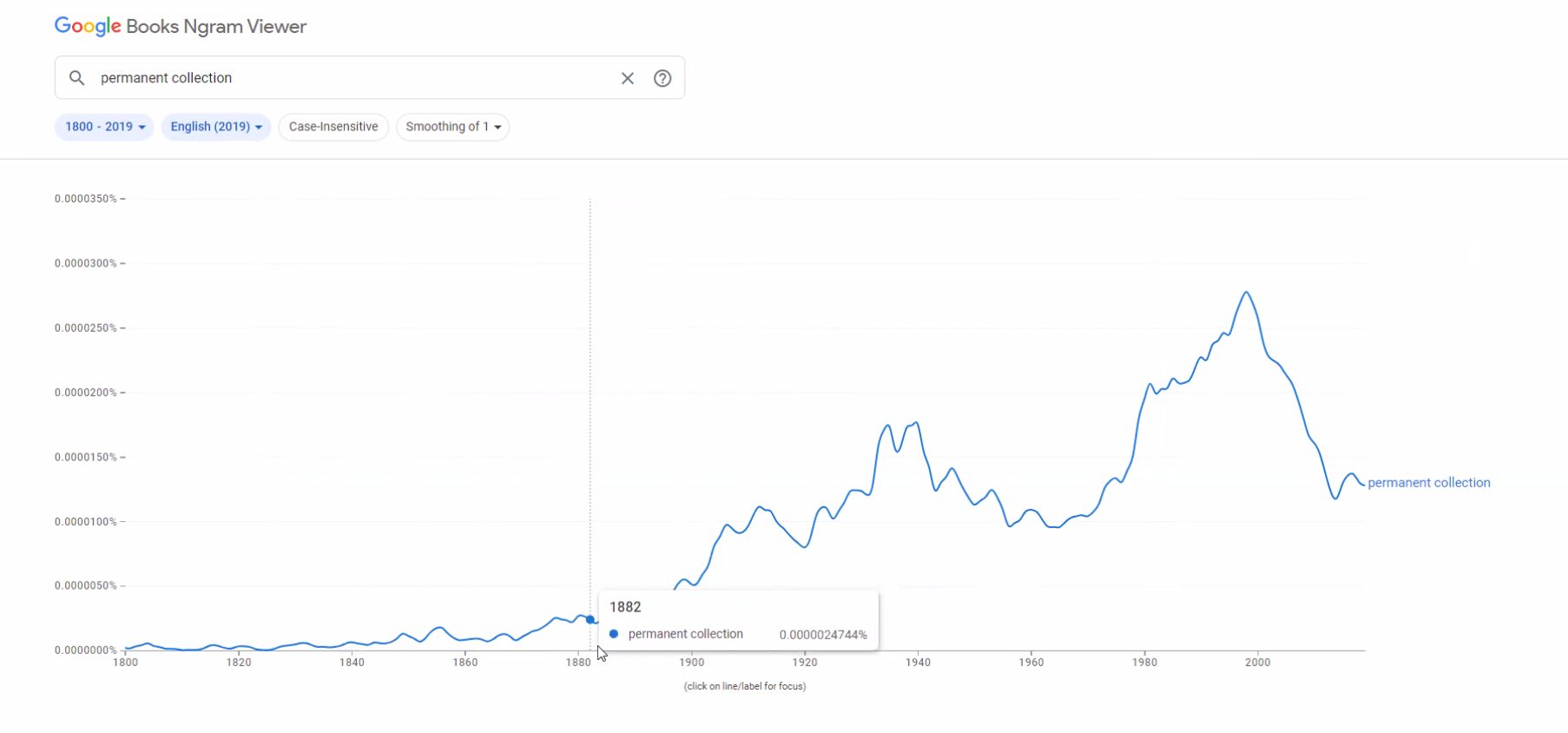

Since 2015, Erin has worked in art institutions helping them thing the policies that should govern what they hold on to, what should be disposed of, and how to think about growing their collections in the future. In that work, she has observed many spaces that were chronically over-filled and under-maintained, and this lead her to think more critically about how museums might imagine themselves while doing a better job of caring for people and planet. As such, the conversation was less focused on prescriptions and more on paradigm-shifting. She questioned what museums are for and what they should be for. She also questioned the “permanent collection” terminology so often used by museums.

“Not everything in a museum deserves to be there or was brought in by someone who knew what they were doing.”

— Erin Richardson

Deaccessioning and Disposal

One of Erin’s areas of focus is deaccessioning. Deaccessioning is the process of moving an item from a museum’s collection. She also assists with disposal, which is the removal of the item (either by sale, destruction, or scrapping) from the institution’s facility. According to Erin, if the purpose of a museum’s collection is to support the institution’s mission in the present and into the future, then deaccession and disposal must be a continual process.

In addition to the challenges posed by a lack of space, maintaining aging items neatly and in a climate-appropriate way is not plausible for a great many museums. The cost of hiring expert staff and the upkeep of suitable facilities often proves too prohibitive — even for larger, better-endowed institutions — such that artifacts in “storage” often fall into decay or go missing in large disorganized heaps. And when so many of these items sit uncared for, they are often also unlabelled, uncatalogued, and unrecognized. The meaning-making work of museums often fails to extend to these forgotten items.

“Museums have so much stuff….holding on to everything would mean building football fields of climate-controlled storage.”

— Erin Richardson

Memory and Museums

Erin also touched on the role that museums and monuments play in helping a society mark a traumatic events — the 9/11 Museum, Holocaust museums, war monuments —- they all serve as tributes to people that were felled in some of our nations’ darkest hours and epochs. That said, what events warrant museums and how long must those museums or monuments stand? Will people a hundred years from now be interested in learning about the events of September 11, 2001 and —-perhaps, more importantly —- will learning about those events help the people of the United States or the world in whatever will be important to those living in the year 2111?

Our group also looked at recent US tragedies (e.g. the Tops supermarket shooting in Buffalo, NY and the massacre at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida) and wondered if there were, perhaps. other mechanisms for commemorating and honoring victims of heinous crimes that didn’t require the huge expense of erecting, staffing, and maintaining yet another building. Still others pushed back with the salient point that it seemed that the resistance to expanding the museum and creating new museums seemed to come right aat a historical moment when traditionally overlooked people —- black people, indigenous people, people in the LGBTQ+ community —- were demanding greater representation. For better or worse, the idea of the museum looms large in the imagination as something that can take an item in and signal to the world that it —- and the people connected to it —- once mattered.

If this sort of conversation sounds up your alley, please sign up to join us at an upcoming Community of Practice gathering.